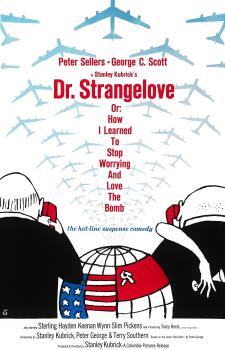

🎥 Dr. Strangelove (1964)

On first viewing, this Kubrick satire can seem as confusing as its title. But some persistence and exploration on the part of the viewer reveals overtly sexual themes coupled with cold-war era nuclear anxiety to provide a mind-boggling ending.

Back in the sixties, the threat of nuclear war was more a question of ‘When?’, and not ‘If?’ That warped mental state, must be similar to what we’re feeling under the lockdown in the COVID-19 pandemic. One only gets desensitised under continued passive threat to life. So it is only natural that the arms race between the United States and Soviet Russia gave rise to such a weird and twisted piece of art.

The movie’s dominant theme is that of the sexuality of the various men involved. My naivete didn’t let me parse any of it in the first viewing and I was later enlightened by some online explanations. Now the myriad phallic imagery is hard to unsee, even in my head. The mid-air refueling hose, the missiles, the Brigadier’s cigar and machine gun are all examples of Kubrick telling you that it is a Man’s world. The women are mere props and the biggest metaphor for women, Mother Russia, is being involuntarily penetrated by US missiles. This comparison is finalized when we see the American president plead and cower on call with the Soviet Premier, almost as if apologizing to his wife.

My own pet theory is how well the three POVs map to the triad of the Body, Heart and Mind. The film opens with the breath-taking visuals of refueling a bomber in mid-air. The similarity to coitus only emphasizes the appendage-like nature of the aircraft in the American military. Even the mechanical tedium of the crew going through the bombing protocol is similar to how the human body’s biological machinery functions.

The next perspective is that of the Air Force Base commanded by the Brigadier. He somehow buys into bizarre claims that his ‘essence’ is being polluted by the commies. His subsequent order to bomb Russia represents an outburst where the Heart acts out all irrational and biased. There’s also the contempt towards politicians voiced as: “War is too important to be left to the politicians.” We even have a conscience present in the form of the RAF exchange officer, who helplessly tries to convince the Brigadier to recall the attacks.

When the news of the attacks reaches Washington, we see the Heads of the State rise from their stupor. These politicians represent the minds behind the entire military operation. Their own emotions have sneaked upon them and now they must go into damage control mode. Launching an all out attack on its own Air Force Base to extract the Brigadier, the Mind violently yanks control of the Body from the Heart. But it is too late, the bombers are on their way. The politicians then attempt diplomatic negotiation, scientific miracles and consultation of think-tanks. These only result in further confusion and infighting amongst the intellectuals, while the bomb steadily makes progress. This futile mental back-and-forth is pithily captured when the President exclaims: “Stop! You can’t fight in here! This is the War Room!”

There are also other minor themes that help prop-up the plot. There is the satirical nod to capitalism where the Coca-Cola company (appropriately) interrupts the salvation of Communist Russia. The film’s title as an offhand note to stop worrying is also no coincidence, alluding to the doctrine of ‘mutually assured destruction’. It promises that if a nuclear war were to break out, it wouldn’t last long or leave anyone behind. Thus, there wouldn’t be much to live for.

Effectively, Dr. Strangelove is a powerful blend of game theory, visual metaphors and political satire. It is repeatedly watchable, allowing for the discovery of something hidden in the dialogue or the visuals.

Rating: (Very Good)